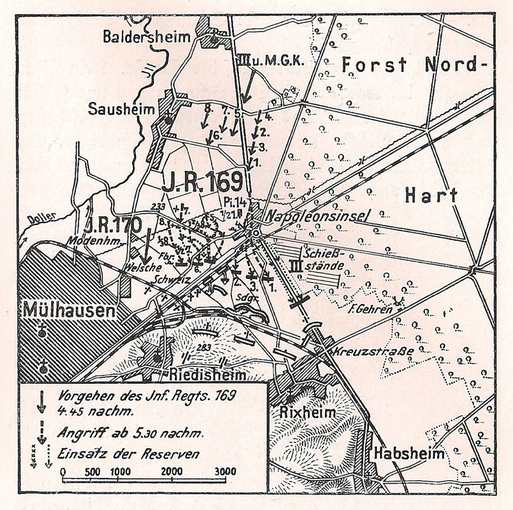

The IR 169 advance pushed over Rhine Canal by the Napoleoninsel Train Station and into an ill-fated charge against strong French positions on the Riedisheim/Rixheim heights.

The IR 169 advance pushed over Rhine Canal by the Napoleoninsel Train Station and into an ill-fated charge against strong French positions on the Riedisheim/Rixheim heights.

“One would hardly believe that it would come to a war. We were of the opinion that the thunderclouds would move away once more, and we told ourselves that no one would take the responsibility to call for a war involving the entire world.” August 2, 1914.

These are the words of Albert Rieth, a trumpeter with Imperial Germany’s Infantry Regiment 169 (IR 169) in the opening days of the First World War. In less than a week, the troops of IR 169 would be thrust from their comfortable garrison town on the edge of Germany’s peaceful Black Forest into the horrors of one of the first major bloodlettings of World War I – the Battle of Mulhouse. (In the immediate hours of the war, the French sought to reclaim the long-disputed Alsace-Lorraine territories. A French Task Force went forth and captured the city of Mulhouse, situated near the Rhine River on Germany’s southern border.)

The Germans XIV Corps, comprised of 44,000 troops based in the southern state of Baden, was the hammer of the Seventh Army strike force. One of the ten infantry regiments in XIV Corps was IR 169, of the 29th Division. With a pre-war strength of 3,500 troops, IR 169 spent the opening week of the war readying for combat deployment. Albert Rieth’s journal describes his battalion’s departure from the garrison town of Villingen and the nighttime journey through the center of the Black Forest.

“Finally the time to march out arrived, August 8, at 3:00 am. We marched to the train station where naturally the entire town was present to wish the young battalion the last farewell. We embarked with the song "Must I Then Leave the Little Town." The train started moving and the song finally diminished. One could only hear the vague hum of the wheels, and some told high-spirited jokes. But most thought about their loved ones, and some thought of the words “Who knows if we will ever see each other again!” The regiment assembled at the Rhine river town of Neuenburg, 20 miles northeast of Mulhouse. Rieth’s journal continued: “No sooner were we with our quartering hosts, the order came for me to report to the captain, and before long I had to give the 'charge' bugle call, as we were ordered to man the trenches across from the Rhine bridge. We heard the first cannon thunder from Fortress Istein, and it felt like maneuvers, but we learned differently the following day. It was our first mission to protect the bridge over the Rhine at Neuneburg and to man a trench on the other side forming a great arc. The night was perfectly quiet, except for the sounds of Fortress Istein grumbling madly all night, the mysterious rushing of the Rhine, and the firm footsteps of the soldiers continuously crossing the bridge to hold the loyal watch on the Rhine.”

The French army, now alert to the coming German attack, prepared a hasty defense across a 15-mile long front. The French line extended 9 miles out from Mulhouse and continued east atop the heights at the suburb village of Riedisheim. Control of the high ground at Riedisheim was particularly significant, as it covered the Rhine canals that served as a natural obstacle to any enemy attack.

The Seventh Army intended to make a two-pronged attack on Mulhouse beginning in the early hours of August 9. The two divisions of XV Corps were to attack the French left on the outskirts of the city while XIV Corp’s 28th and 28th Divisions would directly strike Mulhouse and the high ground on the French right. The miserably humid weather rendered ten percent of German combatants down as heat casualties. Rieth wrote of IR 169’s advance from the Rhine River to the attack assembly area. “Finally, on Sunday, August 9, we vacated the trench at 6 am and moved in the direction of Mulhouse, where there were already small skirmishes between advanced guard posts. We marched along a seemingly endless straight road, and the sun burned down from the cloudless sky, making the march almost indescribably difficult if one considers the heavy load of equipment of an infantryman. In addition the new boots were burning and gave you the feeling of walking barefoot through a mowed cornfield. The cannon thunder came nearer, and soon we could distinguish rifle fire as we marched along the street that led to the canal of Mulhouse. We then saw a picture of an endless column settled upon by a cloud of dust. There was not a bit of air and it seemed like we were suffocating. Some of the men were becoming quite pathetic, with their legs staggering as if they would collapse. Although each one pulled himself together, their faces looked feverish as if a heat stroke was imminent.”

The heat contributed to significant delays in the German advance, and it was not until late afternoon that IR 169 finally neared its attack point. The regiment’s task to secure Hill 283, a steep mass on which sat the small crossroad village of Riedisheim. A canal section and railway station known as Napoleonsinsel stood in the path of the German advance. To close in with the French defenders, the Germans would have to cross the canal and rail embankment and then advance nearly one mile across the open terrain. The German intelligence assessment that this position was held by only a weak picket line could not have been more erroneous. The French entrenched on Hill 283 owned a commanding field of fire with plenty of infantry, supported by machine-guns and artillery, prepared to defend it.

IR 169’s advance guard fanned out through the fields and farmland as the three infantry battalions marched in a long column along a dirt road. The dust rose in huge clouds, choking those troops in the trailing companies. Nearing Napoleoninsel, the regiment went into attack formation, with 1st Battalion (Companies 1-4) on the left, 2nd Battalion (Companies 5-8), on the right, and 3rd Battalion (Companies 9-12), along with the regiment's machine-gun company, following 1st Battalion as the regiment’s reserve.

Albert Rieth, serving as the trumpeter for the 9th Company Commander, wrote of the battle’s opening moments: “Suddenly the order came to rest rifles near the train station of Napoleoninsel, one of the last stations before Mulhouse. We stacked the rifles and fell asleep by the side of the road because of the terrible exhaustion. All of a sudden a hissing and terrible burst, the first enemy artillery shell landed in the canal, causing a great fountain. But we could not admire this spectacle because soon a second, a third, and finally a downpour followed so that we quickly sought cover behind the railroad embankment. We could not deploy, as only a few would have made it across the embankment, so we could do nothing but stay behind it.”

The French let loose a terrible fury of rifle, machine-gun, and artillery fire across the entire regimental front. On the German right, the exposed four companies of 2nd Battalion were fully engulfed in the firestorm. Three of the four companies were soon trapped on the far side of the embankment, with the 7th Company’s commander and executive officer immediately killed. In the space of moments, one third of IR 169’s strength was immobilized. On the regiment’s left flank, the 1st and 3rd Battalions crossed the canal and took cover on the railway embankment by the train station. The 1st Battalion charged over the embankment and were ripped to pieces as soon as the men crossed over the train tracks. Just minutes into the battle, two thirds of the regiment were pinned down only years past their starting point while absorbing heavy casualties.

The 3rd Battalion, along with the regiment’s machine-gun battalion, were ordered into the maelstrom as nightfall approached. This attack made only slightly better progress before starting to falter. Rieth wrote what happened next: “Our captain and battalion adjutant were killed because they had remained in a dangerous position too long, and thus died the hero’s death after only being in battle for less than half an hour. The major wanted to advance with a company but it was impossible, he too soon came back with a bullet hole in his lower body. Our regimental adjutant was hit on his horse while he was relaying an order, with a fragment of shrapnel caving in his skull. 3rd Battalion was just about to retreat when our major appeared with a dangerous wound in the abdomen. Holding his saber in his fist, and without a uniform jacket, he shouted to us: "Men before we retreat from these scoundrels even one half step, we should all wish to die!" This had a powerful effect, and with a "hurrah," we went over the embankment. One platoon of the company had to remain back to give cover for the four machine-guns. The machine-guns fired murderously, but since our fighting line had advanced already, we also had to go forward.” To follow the front lines, we crossed the yard when a terrible shelling came through the roof of the paper factory and exploded in the yard where we were. We had no choice but to leap across the yard. We made it just in time because a new steel rain began. I laid flat on the ground behind a big bale of paper stacked by one of the buildings. There I had the dubious pleasure to hear and see what artillery shells look like when they detonate at a distance of 3 - 4 meters away. I believed the earth was torn to pieces, and the shrapnel flew about my ears so I could neither hear nor see.”

The factory, blasted by a crossfire of both friendly and enemy artillery fire, collapsed upon Rieth. Dazed, he lay trapped in ruins through the night and recorded this scene the following morning: “During dawn I crept away from the factory through a small aperture. But what a view presented itself there, I still think about it with a shudder! A few steps away from me lay a rider and his horse, both dead, and a musician’s carriage totally shot to pieces. This was my road to reality after I had spent the whole night half unconscious under the debris. Soon I met a comrade from my company and went with him to the train station in Napoleoninsel. There lay our captain and the battalion adjutant; both had suffered to their end.”

Although IR 169 made little gain in its attack at Riedisheim, the Seventh Army was able to fracture the French lines in other locations before Mulhouse. French commander Bonneau, despite being able to push off the worst of the German attacks, feared his forces were at the breaking point and retreated back to the protection of the Belfort fortresses. The Alsace remained in German hands for the next four years and finally returned to French control after the German Empire’s defeat in 1918.

Mulhouse casualties were estimated at 4,000 French and 3000 German losses. IR 169’s toll was severe, with the regiment’s field journal listing 23 officers (8 killed) and 544 enlisted men killed or wounded. Much worse bloodshed would soon follow. In the next three weeks, bitter struggles in the Battle of the Frontiers at Sarrebourg and Baccarat cost IR 169 another 1,650 casualties. By the end of 1914, IR 169’s attrition rate was over 100% of initial strength. Albert Rieth was fortunate to survive the war. In January of 1915 he was wounded at the Flanders’ Battle of La Bassee and was discharged from further service. He emigrated to the United States in the mid 1920’s and resided in Providence, RI, where he died in 1970 at age 78.